Tokenism as a Symptom of System Change Failure

By Katherine Sanders

Clubhouse Conversation, January 5, 2021

I have the privilege of hosting my second Clubhouse (CH) conversation tonight, Leading System Change, with Dr. Aekta Malhotra.

Dr. Malhotra is a psychiatrist in Texas who has recently opened her own practice, Apollo Psychiatry. She’s also a visionary change leader and anti-racist consultant, working toward a better healthcare experience for her patients, her colleagues and herself.

Each week I’ll share the systems thinking concepts I discuss in CH so people can refer to handouts and/or revisit concepts whenever they like. I also realize that most people don’t have access to the CH app yet, so these posts are another way people can access the content we share.

Tonight Dr. Malhotra will introduce the concept of tokenism and we’ll discuss tokenism through the lens of systems thinking.

Tokenism

Tokenism Definition: The practice of doing something (such as hiring a person who belongs to a minority group) only to prevent criticism and give the appearance that people are being treated fairly. (Merriam Webster)

Dr. Malhotra shared this short article on tokenism from Fast Company and another short piece on tokenism’s impact on health.

Foundational Systems Thinking Concepts

Reading these articles about tokenism, I started to wonder if there is such a thing as unintentional tokenism? (I will ask Dr. Malhotra and the group that question tonight.) The reason that question comes up for me is because most change initiatives fail. (It’s estimated over 70% of organizational change initiatives fail.) I’m starting to think that if it is unintentional, tokenism might be a symptom of system change failure.

If people from an underrepresented group are brought into a work system with the intention of increasing inclusivity, diversity and equity, but that’s ALL that’s done, the rest of the system will continually reinforce and eventually overwhelm the new initiatives.

Work Systems Model

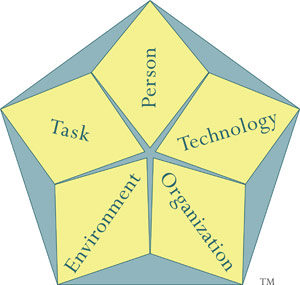

In order to address systemic racism and inequities we need to do more than bring in new people. We need to examine each part of the interdependent system. Unless we address the design of the work itself, the technologies people are asked to work with, the social and physical environments people are working within, and the organization’s policies, procedures, reward structure, profit model, culture, history, etc., we can’t expect interventions in only one or two areas to take root as we’d hoped.

(See the work systems model and learn more about my healthy work framework if you’re interested in what creates health in a work system.)

Systems, however dysfunctional or healthy, come to some homeostasis. If we only invite new people with new ideas, perspectives, needs and talents into an existing system, we can expect that the rest of the system will eventually wear them down, either exhausting them so they conform to the existing system, or demoralizing them so much that they end up leaving.

Thus, some institutions who have worked on their ‘diversity pipeline’ for decades, have a revolving door of talent. They wound the people who accept their invitations to ‘bring diverse perspectives’ into the conversation. Those institutions might have invested heavily bringing people in, but they never invested in designing responsiveness, inclusivity and congruence into their organization so that the new people can evolve the organization.

These aren’t new ideas. Decades ago, researchers were finding that bringing new people into established systems seldom had a reforming impact. In Making Differences Matter (Thomas & Ely, 1996) explain the differences between three paradigms:

- discrimination & fairness

- access & legitimacy

- learning & effectiveness

Essentially, the first two paradigms involve the old practices of bringing fresh talent and innovative ideas into an existing system and observing while the system, predictably, crushes the life out of the people and their ideas. The weight of ‘the way things are’ can’t be overcome, especially by newcomers.

The third paradigm they describe is one of organizational change – where the system itself is meant to change and evolve because it is informed and driven by its people. Although the examples Thomas & Ely cite from the 1990s aren’t compelling (to me), the concept behind it is.

We can design our systems to respond to our people. We can intervene systematically to uproot inequitable and unhealthy practices, procedures, technologies, job designs, profit models, reward systems, and work environments. We can support our talent – new and existing – in finding the leverage points for change so that our systems become both more effective and more sustainable – doing less damage to employees, clients and the environment.

We know how. We’ve known how for decades. When we decide to take action, we will see sustainable and life-affirming change.

To Learn More

To learn more about systems thinking and how to shift work systems toward greater health, check out my online programs and free resources. I’ve also started a new membership group, Leading System Change, for change agents seeking inspiration and support in a systems approach to change.