Humane Change

By Katherine Sanders

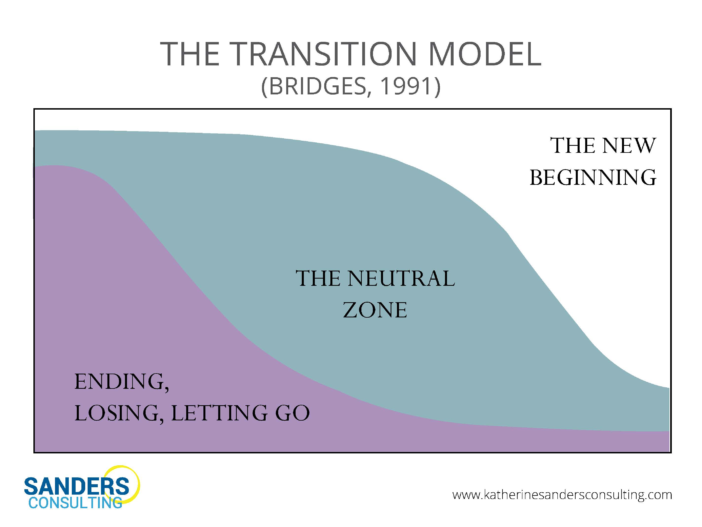

My friend and colleague, Karen Konrath, uses a model from William Bridges in her executive coaching practice to talk about change.

She explains that change happens quickly at work, many times without our desire or consent. Your project falls through. Management downsizes your group. You are assigned a new boss. But, even though our external circumstances are new, really internalizing that change requires that we take an inner journey – a transition to a new reality.

Bridge’s model describes the inner transitions people make in response to changes in the outer world. It starts with the loss of the old way of being, acting and thinking. We then enter a neutral zone, the in-between time when the old ways are gone, but the new ways aren’t fully functional. It might feel chaotic, stressful, like traveling in a fog.

The new beginning starts when people develop their new identity, experience hope and new energy. They feel a new sense of purpose. This is where people start believing that the change can work for them, and they participate in making it work for the group.

What I love about this model is that Bridges highlights a phase of the change process that most of us (especially at work) prefer to skip over – letting go of the past. And in emphasizing this important first step, he adds something tremendously important to the organization change literature.

No one likes to deal with loss. And the idea of acknowledging loss and grief may be especially uncomfortable at the workplace, where we like to pretend people are solely rational beings.

I believe some people are afraid that if they start to acknowledge and express their feelings, it will never end. They’ll fall into a well of pain so deep, that they’ll never climb out. So what we typically find in organizations are a lot of wounds that have never been acknowledged, festering under the surface, waiting to be attended to – released and healed.

Here’s where trust comes in.

We have to trust that when we start to grieve, we will find an end point. There will be a beginning, a middle and an end. We may be changed forever. If it’s a severe loss, we might start by learning to breathe alongside the pain. If it’s less severe, we might be able to find the benefits in the changes relatively easily – not only what we’ve lost, but also what we’ve gained.

We have to remember that grieving is part of healing. It’s natural. It doesn’t need to be dramatic. We acknowledge what’s already happened. Grieve its loss. And then we are more able to let go – of ideas, ways of being, behaviors, expectations and former identities.

In order to do this, we have to learn to tolerate some discomfort. Discomfort within ourselves. Discomfort in our working group while others are going through their own internal transitions.

What effective change leaders know is that we successfully transition because of dealing with grief, not by ignoring it. It is only when we allow ourselves and others to truly grieve, does space open for other feelings and experiences to resurface – acceptance, curiosity, hope.

There might be some heaviness as we start our journey into the unknown. But the price of not factoring in this phase is high. (Think of those colleagues whose stories of loss and victimization have become their identity.) If we want our change initiatives to work, we must support people through transitions.

We can’t ignore people’s emotions.

It might seem odd that a human factors engineer would write a post about emotions in the workplace, and maybe it is. But it’s also practical. When we ignore the parts of the work system (like people’s emotions about what’s happening at work), we are pretending that the system is something other than it is. We are fooling ourselves. People aren’t objects to be moved. People have emotions, needs and limitations. Health-promoting work systems design structures and processes to support and respond to human needs and desires.