Trust as a resource

By Katherine Sanders

I talk a lot about the design of healthy work systems. But what actually determines whether or not a work system is healthy or unhealthy? One of the fundamental ways to tell is whether or not people have adequate resources to meet the ongoing demands of their jobs, and can control those resources.

The term ‘resources’ here means a whole host of things – having the time, energy, skills, abilities, autonomy, staffing, social support, budget and materials needed to do what we need to do. Without these resources, we just can’t continue to rise to the challenges we face.

I’d like to add trust to our list of necessary resources. Not only because it makes some of the other resources possible (without trust, there is no social support), but because I believe trust in ourselves is vital. We have to have confidence in our resources and needs. We need to trust that when we need to ask for additional resources, not only is it likely we will receive them, but we know we are deserving.

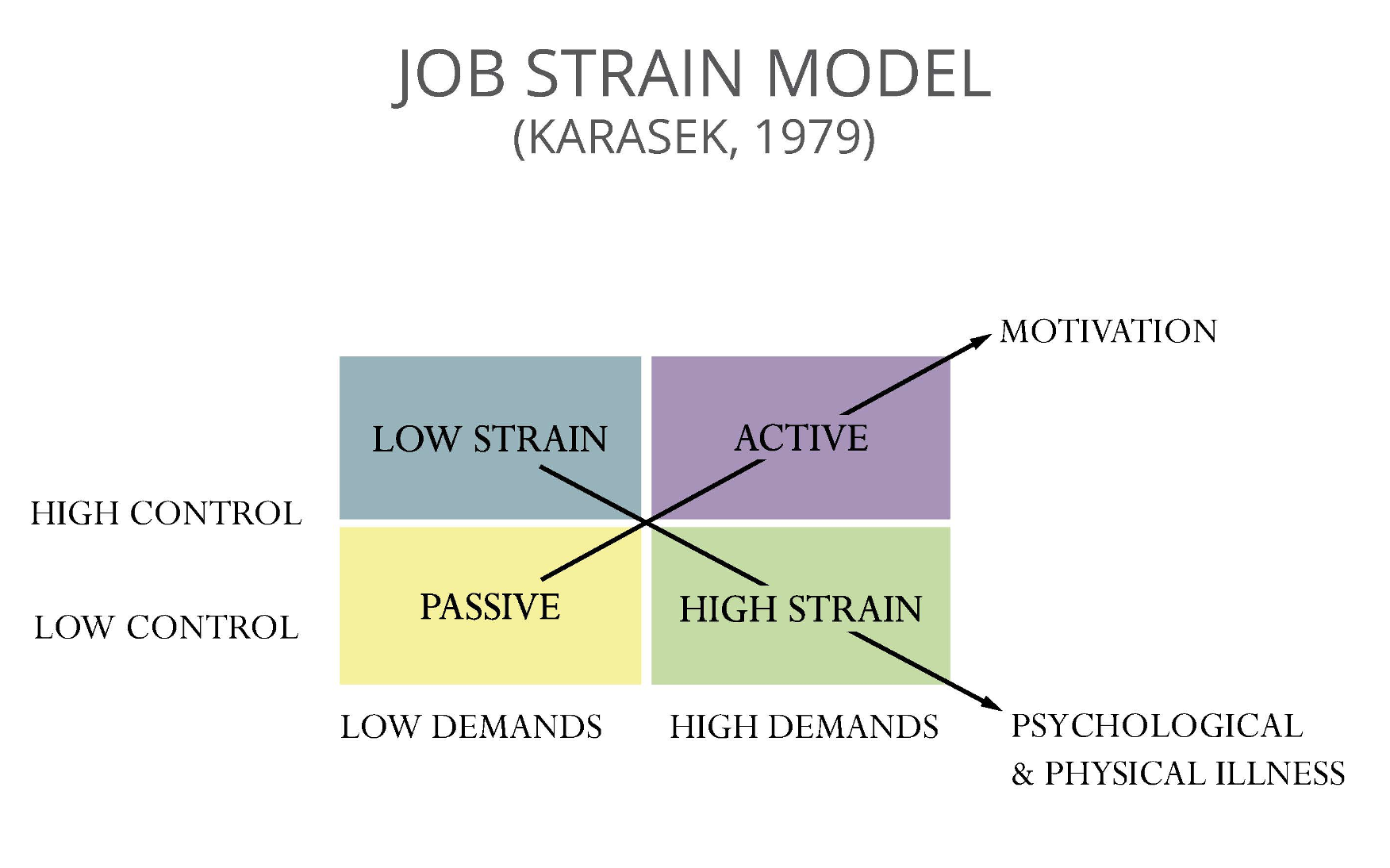

It’s vital we ask for and receive these necessary resources, not only for the sake of the work we’re trying to accomplish, but also for our own health. Robert Karasek studied the cardiovascular health of large working populations over decades and found that the relationship between our job’s demands and the control we have over necessary resources significantly impacts our health. His Job Strain Model illustrates his findings.

The concept is elegantly simple. When we are faced with high demands, we can rise to meet them if we have the resources to do so. But if we are faced with ongoing challenges and have low levels resources to meet those challenges, we eventually become buried by them and our health suffers. These are the jobs that put people at risk for physical and mental illnesses. Burnout.

Karasek’s model can give us insight into our own jobs, their impact on our health and what we can do about it.

Here is a list of resources that allow us to meet work demands:

- Proper skills

- Appropriate education

- Enough work time

- Enough rest time

- Adequate staffing/assistance

- Adequate budget

- Autonomy in how we do the work

- Autonomy in when/where we do the work

- Social support (both at work and at home)

Karasek describes four categories of jobs:

Active Jobs

When we experience high demands and high levels of control over the resources needed to meet those demands, we’re thought to have an “active” job. These kinds of jobs usually correlate with an increase in what we have recently come to call “employee engagement.” Healthy work systems design jobs that fall in the active category.

Passive Jobs

When we experience low demands and low control over resources, we’re thought to have a “passive” job (think of a toll booth operator at night who can’t leave the booth until the end of the shift). In these jobs we’d expect people, if allowed, to be doing other things – reading, talking on the phone – in order to keep themselves awake and alert. Passive jobs lead to low levels of motivation to do “better.” There’s just not enough content to keep people engaged.

Low Strain Jobs

If we have low job demands and high levels of control over resources (say, a part-time sales position), we have what’s considered a “low strain” job. These types of jobs provide employees with some sense of freedom and flexibility. They can decide how to do their work so it’s best aligned with their preferences, for example. And they have ample resources to meet the demands.

High Strain Jobs

Where we get into trouble is when we have high demands and low levels of control over resources. People in these “high strain” jobs, where the demands consistently exceed their resources, are at higher risk for mental and physical illness. Specifically, Karasek’s research showed that people in high strain jobs had higher risk of cardiovascular disease. (In the decades since, we’ve learned much about why and how people get ill in high strain situations. If you’re interested in how stress affects health, consider the classic book, Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers or watch this documentary featuring Stanford professor, Robert Salpolsky.)

When we talk about “trust,” we’re usually not thinking in terms of resources that help us get our jobs done and stay engaged. But I think it deserves to make the list.

After all, a number of the other resources require it.

- We need to trust in our own skills and abilities – to have the confidence to know that we can do what we’re asked to do.

- We need to trust in the capacity and willingness of those around us – to support us, and to step in when we need help, or even just give us a pep talk. Tell us we matter, that we can do this.

- We need to know that people trust us – so that we can take risks and put ourselves out there. If our boss or co-workers make it okay to take a risk , and sometimes get it wrong, we’re much more likely to take a creative approach.

- Most importantly, we need to trust our own assessment of our available resources – do we have enough time, energy, skills, social support, and autonomy to really do this? If not, we have to ask for help. Asking for help can be liberating. Asking for help can be a radical act in some organizations, or for people who were taught that we’re all meant to be self-sufficent.

The truth is, we’re all in this together. We all feel overwhelmed at times. And some of us are working in poorly designed work systems, where most people feel overwhelmed most of the time. If you’re in such a system, a first step is to acknowledge it, and to start a conversation, “Is there another way?” Because there is another way. There always is another way.